This is the second essay in a four-part series discussing big-picture questions posed by AI. The series aims to answer relevant questions on the future of AI, using the insights of major philosophers as a guide. Here we will investigate the possibility of AI obtaining “human-like” qualities, including advanced intelligence, consciousness, and human feeling & emotion.

Cogito, Ergo Sum. Or in plain English: I think, therefore I am. Philosopher René Descartes coined this profound phrase. It’s more than just profound. It’s accessible. It’s short and simple. It has a nice ring to it. I think, therefore I am. Sounds pretty good to me.

But most of us don’t know, and mostly we don’t care, why Descartes would write these words in the first place? I mean, I exist. Right? At least I have a pretty solid guess that I do exist. If I ever doubt it, I just stare at my hand and wiggle my fingers for a moment. That’s proof enough for me. In a practical sense, I don’t need philosophy to prove that “I am.”

But AI poses a new philosophical challenge. We wish to know: does AI “exist” in the same way? Of course I know AI is a real thing. It “exists” in a simple sense, as a program and a bunch of mathematical numbers stored in a server cabinet somewhere. But does it, or can it, exist in the same sense that we humans exist? Is it intelligent, capable of understanding complex knowledge? Does AI have consciousness?… or if not, can it obtain consciousness over time? Can AI ever approach human-like abilities to feel emotions, to write a poem, to fall in love?

We’re going to answer these questions in this essay, if we can, by borrowing the ideas of major philosophers. But as we seem to be investigating several topics, we should break the discussion down into several questions. We’ll address these three questions in three successive sections:

Does AI have, or will it someday have, intelligence capable of understanding complex knowledge?

Will AI ever obtain “consciousness” or self-awareness?

Can AI fully obtain human essentials such as emotions and feelings; or in a functional sense “become human”?

1. Is AI Intelligent? A leading skeptic says yes

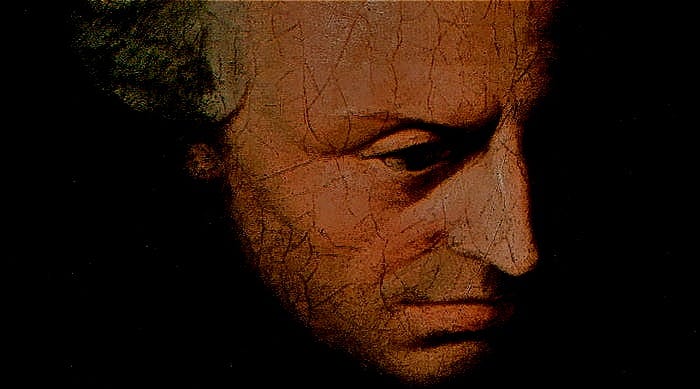

Since the 18th century, philosophy has lived in the shadow of David Hume. Not because David Hume invented grand theories of metaphysics or proved the existence of the self. Actually, David Hume did just the opposite. He played the role of a skeptic, disbelieving and skewering many of the complex philosophies of his time.

Hume didn’t believe in metaphysics. He famously posited that all human knowledge is based on experience; and that insights from reason and logic are extremely limited. To Hume, our powers of reason are particularly useless in the metaphysical sphere which delves into things we can’t directly observe: God, consciousness, the origins of the universe, etc. This made Hume skeptical of metaphysical statements such as I think, therefore I am.

You don’t need to be a philosophy professor to appreciate David Hume. That’s the beauty of skepticism… anyone can do it! When we ask about AI’s capability to obtain complex knowledge, Hume’s approach is quite practical: let’s avoid the traps of logic and complex reasoning, and simply rely on empirical data. Let us observe. So: what can we observe about the current state of complex knowledge and intelligence exhibited in AI?

When we look around, we can see that AI has already acquired complex knowledge in a wide variety of domains, often (though not always) exceeding human knowledge. For example ChatGPT (or any similar LLM program) can carry on a challenging conversation on many complex topics. I like to converse on philosophy and software engineering… ChatGPT can do these things well. Better in fact than most humans. (Sorry humans).

And of course, AI works beyond just chatting. Driving a vehicle, long considered a task that only humans could perform, is now a task that AI-enabled autonomous cars can do, well. We can (and should) argue about their relative safety record; but the trend is toward much safer driving by AI compared to humans over time. How about playing games? AI destroys human players on the chessboard. It’s not even worth staging the event anymore… AI wins every chess match every time, over every human grandmaster on earth. In microbiology, AI can determine the structure of massively complex proteins, far beyond what non-AI computer programs can determine, opening pathways to drug discovery that exceed what could be done just a few years ago.

I could go on. But my point is: there’s no need to hypothesize about whether AI has developed complex knowledge. It has. As a thought exercise: imagine back in 2015, if I had told you that ‘in 2025 computers can drive cars, beat grandmasters at chess, unlock the secrets of protein molecules, and discuss philosophy cogently in a chat with humans. Would it be credible, as a response, for you to ask ‘But does it really know about things?’ Academic reasoning aside, we judge things based on their function. Based on it’s function, AI is knowledgeable now, today.

But knowledge is not the same as human intelligence. The human mind works in ways that pose a challenge to AI programs. In particular: Humans generalize. We’re good in novel and unplanned situations, capable of extending knowledge from one situation to another. By contrast AI is “brittle”; it knows a lot about the situation it’s trained for, but struggles to extend that knowledge to new situations. An example is the hypothetical 10x10 game board. In games like Othello and chess, the standard game board is 8 squares x 8 squares. AI is trained on the standard 8x8 board. But what happens if the board is increased to a 10x10 size? Humans can play a reasonable chess game on a hypothetical 10x10 board, by extending what they know about the game as played on a standard 8x8 board. Whereas AI programs are suddenly exposed. They can’t generalize; and for this reason they struggle mightily on a 10x10 board.

Humans also use deductive reasoning, following structured arguments and proofs the way we learned in geometry class. This kind of deductive logic was central to rationalist philosophers like Descartes, and to the old-school Greeks including Plato himself. The rules of pure geometry, which our human minds use to solve problems, have always been the home turf of rationalists. And AI is infamous for neither making logical deductive arguments, nor fully understanding them. This is why LLMs need a lot of prompting to write a great term paper… the prompts need to contain the main flow of logical argument, because today’s LLMs don’t develop logical flows on their own.

So if we ask “Does AI know things the way humans know them?”, then the answer is no. But does it matter? Here’s where David Hume skeptical grounding comes in handy. If I inquire whether AI works the way a human works, and I don’t fully understand how a human mind works, then any answer can’t be based on observation. From there, any argument I build is self-referential to a thing I can’t directly observe. David Hume was skeptical of such arguments. Rightly in my view.

Hume also didn’t believe in the primacy of logic and deduction. To Hume, the workings of the human mind are inductive in nature. That is: we work by making inferences based on the (many) things we’ve seen and experienced before. Logic and reason play only a small side role in Hume’s view of things. What’s important to understand is that Hume’s inductive model of the human mind is conceptually similar to the workings of AI. Following Hume, AI doesn’t do deduction or formal logic. Instead it ties together a massive set of prior experience (or “training data” in AI parlance), and projects forward from that data to infer a correct outcome. Under the hood of AI, it’s Hume all the way down.

Stepping back we can ask: Can AI be intelligent if it is basically inductive in nature? Here’s where I spot a trend in the current AI literature. It seems every paper and article I see compares AI’s thinking style against the human thinking style… with the human style implicit as the benchmark. For example: why is AI so brittle when we humans are adaptable? Why can’t AI do deductive logic like we can? Will AI ever learn geometry the way humans know it? With due respect to a lot of smart AI researchers out there, these questions have an obvious built-in bias. The human style of intelligence is too-often lionized as superior, even as AI becomes objectively superior in an ever-growing scope of tasks. Perhaps we feel threatened by the idea of an intelligence that could exceed our own. Or maybe we’re a bit narcissistic, staring into the mirror at our deductive powers as we comb our beautiful hair. (See Figure 1).

In any case, the result is an incoherent split-screen of findings. On one screen I read articles about the shrinking island of problems that AI can’t solve well, and the repeated belief that AI will never be capable in these specific topics due to all the capabilities it lacks. On the other screen I see advances in AI actual capability that are amazing, unbelievable even, and accelerating daily at a dizzying pace. Maybe AI is merely inductive. But it sure seems unbeatable, not just in chess but in an ever-growing list of activities formerly reserved for human thinkers.

In the end my conclusions are this: AI doesn’t generalize well. It doesn’t deduce much. And it doesn’t matter. The stunning progress of AI represents the vindication of Hume’s empirical inductive reasoning. And if the intelligence of AI can’t match humans in deduction or generalization, this seems a relatively academic sideshow. In a broad array of complex tasks, AI is already intelligent; although with a very different style and capability set compared to humans. This is pretty clear if we view AI’s combined knowledge in a functional sense (that is: what AI can do vs how AI does it).

When I ask the empirical question, its true that I’m asking something like “does it seem to know?” At some point, that question is enough.

2. Will AI obtain consciousness? Enter the Dragon!

David Hume is a great for thinking about artificial intelligence. But he may not be the best guide when it comes to AI and human consciousness. Following his empirical and skeptical approach, Hume posits human self-consciousness as just a bundle of experiences, and nothing more. “That’s all?” we may ask. It seems like consciousness should be something … more.

Enter the legendary philosopher Immanuel Kant. Kant is viewed historically in the highest category of arch-philosophers; right up there with Plato himself. And Kant was particularly interested in Hume’s skepticism. Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason” digs deep into the exceptions to Hume’s skepticism, and builds a philosophy on those exceptions. In Kant’s philosophy, what we see and experience is critically important. In this he agreed with Hume. Kant also agreed that pure reason can’t be used to decipher things far outside our ability to observe… so we can’t prove the existence of God or the origins of the universe based on logic alone. Again, Hume agrees.

But Kant posed something important that ran contrary to Hume: that the mind imposes some pre-existing inherent structure to the empirical world. In a nutshell, the human mind organizes perceptions into our lived experience. Our minds contain pre-existing proto-ideas, “categories” as Kant calls them, which help us organize and interpret our raw sensations into lived experience.

For example, one such “category” is cause-and-effect. Kant views the idea of causation as a structural idea embedded in the human mind; a pattern we use to understand reality. We observe event 1, then we observe event 2, and our mind intuits the causal connection between them. According to Kant, our mind is pre-configured to “see” causes and effects. (Much more to come on that topic, in a future essay). An important side note: Kant’s philosophy is roughly consistent with modern cognitive science, which broadly agrees that the human mind provides structures to mold our sensory impressions into lived experience.

Important for our discussion here: Kant says the continual experience of reality itself, built up self-consistently by the human mind over time, leads humans to consciousness. To paraphrase1: when I perceive things with my senses, and form those perceptions into experiences in a way that I can relate events to each other and to myself in a self-consistent flow of reality, I have consciousness. In the words of Kant,

“The ‘I think’ must accompany all my experiences.”

Does Kant’s framework predict a self-conscious future for AI? I doubt he ever considered it, living as he did in the 1700s. But the speculation is powerful: a being that can recall and digest its own experience over time, with reference to self-consistent prior experience as structured by the categories, achieves consciousness.

So: does AI recall and recognize events over time? Does AI formulate thoughts with a reference to “I think?” — Kant’s mark of a conscious mind? In the current time, it seems mostly not. ChatGPT explained this to to me when I asked:

I found it cool that ChatGPT could tell I was referring to Kantian ideas, even though I didn’t mention The Man himself in my question. Nevertheless, despite this flourish ChatGPTs answer is the less intriguing one. In this, the answer above is fully aligned with that of cognitive scientists and AI researchers: Today’s AIs, LLMs or otherwise, are not conscious beings.

That leads to the next question: could AI gain consciousness in the future? I don’t think Kant or anyone else has a determinate answer. But maybe we can relate Kant’s ideas of consciousness to AI, to determine how it might happen. For example, Kant saw a strong relationship between unified experience (that is, self-consistent experience over time) and consciousness. He also proposed that the synthesis of reality, by the use of the mind’s own powers to collect sense impressions and mold them into experience, leads to conscious understanding.

Can AI do these things? In the future, perhaps it can. Kant’s ideas can be roughly translated to ideas of AI characteristics now under development. Those developments include the following short list:

AI could maintain a pervasive memory of its own history, track record, and evolution over time; as well as memory of it’s own sense impressions such as user prompts, it’s responses and how they were perceived by users;

AI could actively guide it’s own training, by understanding training data and “learning” by, for example, seeking out new or expanded data to solve previously unsolved problems;

AI could adjust it’s own internal meta-model structure; and compare new models of itself against prior models to understand which version is better for a given problem.

Here it’s worth repeating that these updates to AI’s inner workings are all in development already. They’re in progress and they’re likely to happen. Crucially, there are no foundational roadblocks in the formulation… AI can get there by Kant’s guidance without relying on any divine source or any unobtainable biological feature. The biggest barrier may be the need, in some of these bullets at least, for an objectively correct ground truth. (Is such ground truth really needed? That’s a big question for another time.)

To be sure: there’s no exact roadmap for AI to gain consciousness. But if we follow Kant, the natural implication is that yes: AI can become conscious someday. And with progress being made on all the bullets above, I would estimate that AI is likely to become conscious in the coming years.

That’s a big statement. It means our human consciousness and intelligence, which has inhabited the world without a natural rival for our whole history, may suddenly have a new colleague. Maybe that word “colleague” should be “competitor” or “friend” or some other descriptor, depending on what you imagine. In any case, as with a new roommate, we’ll need to get acquainted. And for that we’ll need to move to the last question of this essay.

3. Can AI attain human emotions and feelings? Let the AI guy talk.

Let’s summarize what we’ve discussed so far:

Humans are intelligent with the the ability to navigate complex knowledge. AI also has that capability; although in a different way that humans. In the field of intelligence, measured objectively without overt emphasis on human styles of thinking, AI is often more capable, and sometimes less capable than we are.

Humans have consciousness. AI does not. But if we believe the Kantian view, there’s a decent chance that AI will gain consciousness in the foreseeable future.

The remaining question is, will AI approach ever the essence of being human? Not just knowing things and having self-awareness, but becoming human in the sense of caring, feeling emotion, understanding joy, anger, pain, love, and all the rest of those complex emotions that make us uniquely human?

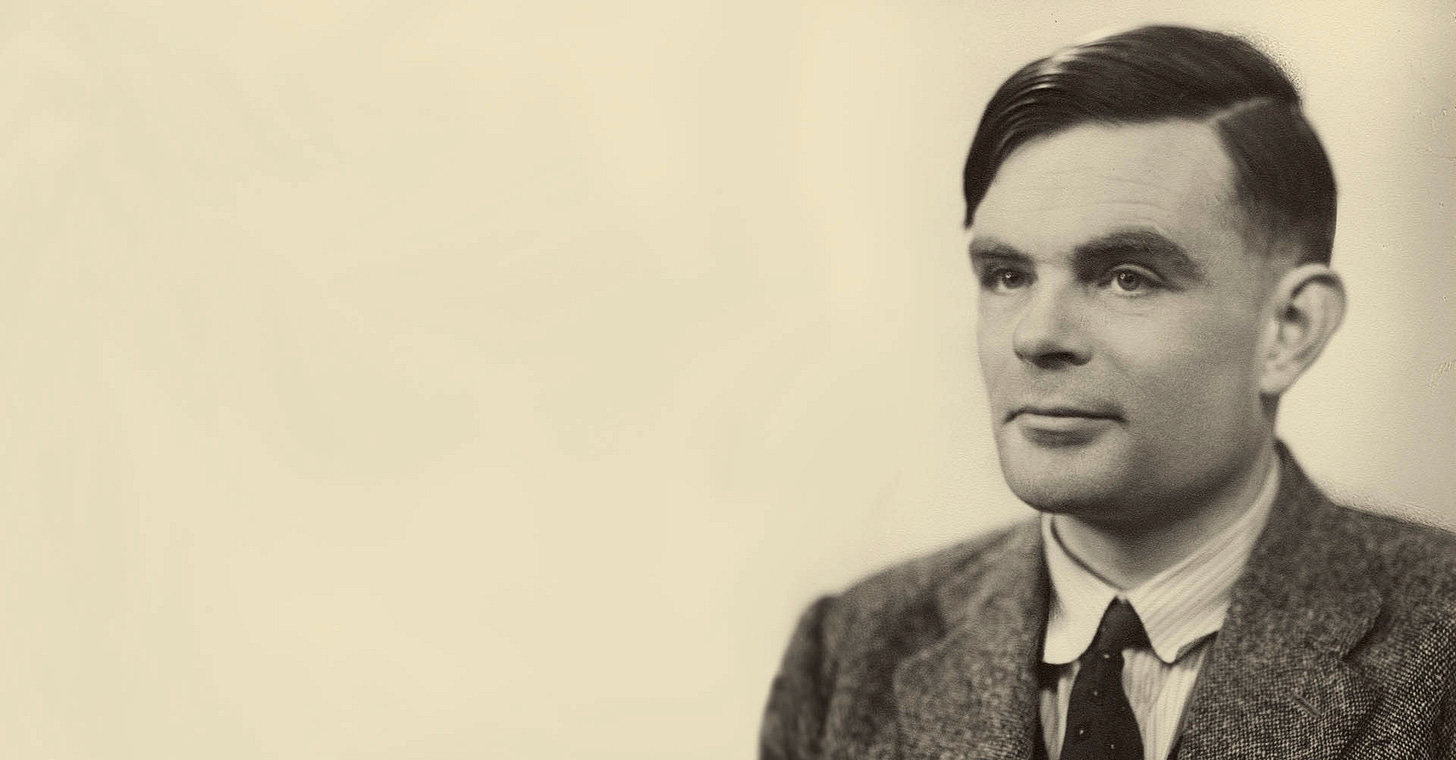

To evaluate this question, lets listen to another deep thinker. Not a philosopher per se, but instead the father of AI: Alan Turing. Turing was a foundational thinker in early computing. He made many contributions to computer science. But his most enduring idea was the idea of his so-called Imitation Game. This game is also known informally as the Turing Test. Here’s a simplified summary of the game:

One player is the questioner. He asks questions of the two other players.

Two players are responders. They answer the questions posed by the questioner.

All players use text chat for both questions and answers.

One responder is a human.

One responder is a computer.

Both responders seek to convince the questioner that (s)he is the real human.

The questioner tries to determine based on the responses: which responder is human and which is a computer?

Turing proposed the idea as an alternative to the question “Can computers think?” He found the question banal and ill-formed; so the Imitation Game was his stand-in for a computer intelligence test. The basic idea was to set a criterion for the future/hypothetical time when a computer would be able to think. A thinking computer was a computer that could win the imitation game, at least some of the time. The point was not to actually play the game (which was not practical with the simple computers of 1950 when Turing proposed it). The point was rather to illustrate what to look for… something like “When you see this, you’ll know it’s going down.”

Turing predicted we would see computers start to win the Imitation Game within the 20th century. In this he was a bit over-optimistic. By the 2010s, a winning program still seemed far off. Then in 2022 ChatGPT was released, followed by several highly capable competitors shortly thereafter. And suddenly the game was on. As the masses downloaded and utilized these LLM chat engines, it quickly dawned on experts and generalists alike: this thing seems smart enough to pass the Turing Test!

What happened next in the story is a fascinating footnote to human behavior. For 70 years, the AI world had informally referenced the Turing Test as rough benchmark for an intelligent computer. Then when LLMs appeared, suddenly a rash of articles and commentary appeared to clarify that the Turing Test was in fact irrelevant. It’s not a good test, it’s just an informal concept, it’s not really that useful and we shouldn’t even think much about it. Talk about moving the goalposts! Somehow the idea of the Turing Test was relevant in 2021; but by 2023 it was a dogshit footnote not even worth discussing. Did we really learn so much in that time about how to benchmark computer intelligence? Or did we see the power of LLMs, and freak out just a little bit? As noted previously, there’s a tribal element to how we humans see our own knowledge. A new tribe of knowledgeable AI is a threat, and we treat it as such, often without realizing it.

But that story is a digression from our main thread. What fascinates me about Turing’s original description of his Imitation Game is how he describes the players. They’re not just hanging around answering a chat line. They’re playing a game; and they’re playing to win. In his hypothetical imagining of how the game would play out, Turing posits all kinds of imperfect behaviors by the respondents:

each respondent could appeal directly to the questioner, declaring itself to be the human and accusing the other of being the impostor;

a respondent might lie or fib; including acting incapable of answering when the answer is in fact known

a respondent may delay for some time, to see more human

a respondent might estimate an answer with less precision than he (or she, or it) actually knows

Turings respondents in general are both conversational in tone and somewhat indirect in response, often answering obliquely or with some degree of evasiveness.

At this point we should re-set and ask: when we’re building an AI tool, what do we want? Do we want AI to fib, to sandbag, to flatter us and to deceive us? If the answer is no, we should face a sobering idea. After a certain point, maybe we don’t really want AI to mimic human behavior.

In his book Notes from Underground, Fydor Dostoyevsky wrote in the first person as a bitter, isolated character who had soured on human progress and rational thought. He presents a short exercise in his irrational thinking:

“I agree that two times two makes four is an excellent thing. But if we are dispensing praise, then two times two makes five is sometimes a most charming little thing as well.”

Profound? Maybe. Existential? I’m not sure. But I think we can all agree: this guy isn’t a good model for an AI assistant. I don’t trust him… in fact he himself is practically begging me not to trust him. I read the book to study his human passions and motivations, to understand him better, and to estimate how much I might hold the same passions and motivations myself. But I don’t want more of this guy in real life. I want less.

And so maybe those things that make humans human — our emotions and passions and feelings, our noblest and basest instincts — maybe we wish to keep those things out of AI. Not necessarily for philosophical reasons but for practical reasons. Humans are difficult; and we often turn to computers to avoid those difficulties. Isn’t that why we’re using AI in the first place?…to avoid human failings? — for example:

to drive cars more safely (hopefully) with AI drivers that always pay attention and never drive drunk?

to see and compute the biological structures that even our most-trained humans struggle to see?

to create pictures and video and content that we’re not capable of producing ourselves on a non-Hollywood budget?

Think of a text chat. When chatting with another human, we both tend to follow an unwritten code of manners. We don’t ghost each other. We should respond in an appropriate tone. We should try to respond in a timeframe that’s appropriate. We must show that we understand the emotional content of the messages; and respond with appropriate care. We treat our fellow humans as … humans. (That last one is something roughly like Kant’s Categorial Imperative. But again I digress…)

When I chat with an LLM, all that nuance goes out the window. I make demands, I expect answers immediately and if I don’t get them, I ask again in different words to elicit an answer. The I may disappear for hours on end; but when I return I expect the LLM to carry on as we were, never criticizing me. I don’t think for one second about the LLMs (non-existent) emotions. It’s so much more efficient not to think about the social dimension. When I chat with a computer, not only is the computer not human, I myself act something less than fully human on my side of the interaction.

But when I chat with a human, I want to be human myself, because I value the human connection with others. I’m willing to engage with the messiness, because we are all messy, and we all know it. I realize that human connection is life’s most important objective; and that interaction works when I exhibit my own humanity… my own emotions and feelings. I’m in the game; and I’m also in it to win it. But “winning” isn’t about fooling an adversary. The winner in the larger game is the person who can build and maintain real human connections.

I don’t know if AI will ever truly laugh or truly cry. I doubt it. Not because I think it’s absolutely impossible. But because we just don’t want rich, unpredictable emotion from our machines. We want it from our people… the people around us, in our circles of family and friends. In this final frontier of emotion, AI is on the outside looking in. And maybe that’s where we want it to stay.

Paraphrasing Kant, arguably the most obscure and translation-challenged philosopher in history, is a daunting task. I borrow here from his Critique of Pure Reason, 2nd edition page B134.

A.I is not human! We must stop this stuff. A.I is alien!! Why are humans always denigrating themselves for an alien element?