The Nature of Truth in the AI Age

Part 3 in the AI+Philosophy Series

This is the third essay in a four-part series discussing big-picture questions posed by AI. The series aims to answer relevant questions on the future of AI, using the insights of major philosophers as a guide. Here we will investigate the concept of truth, and how truth comes under pressure in the coming AI-driven future.

“Truth is universal, objective, and intelligible only through reason…”

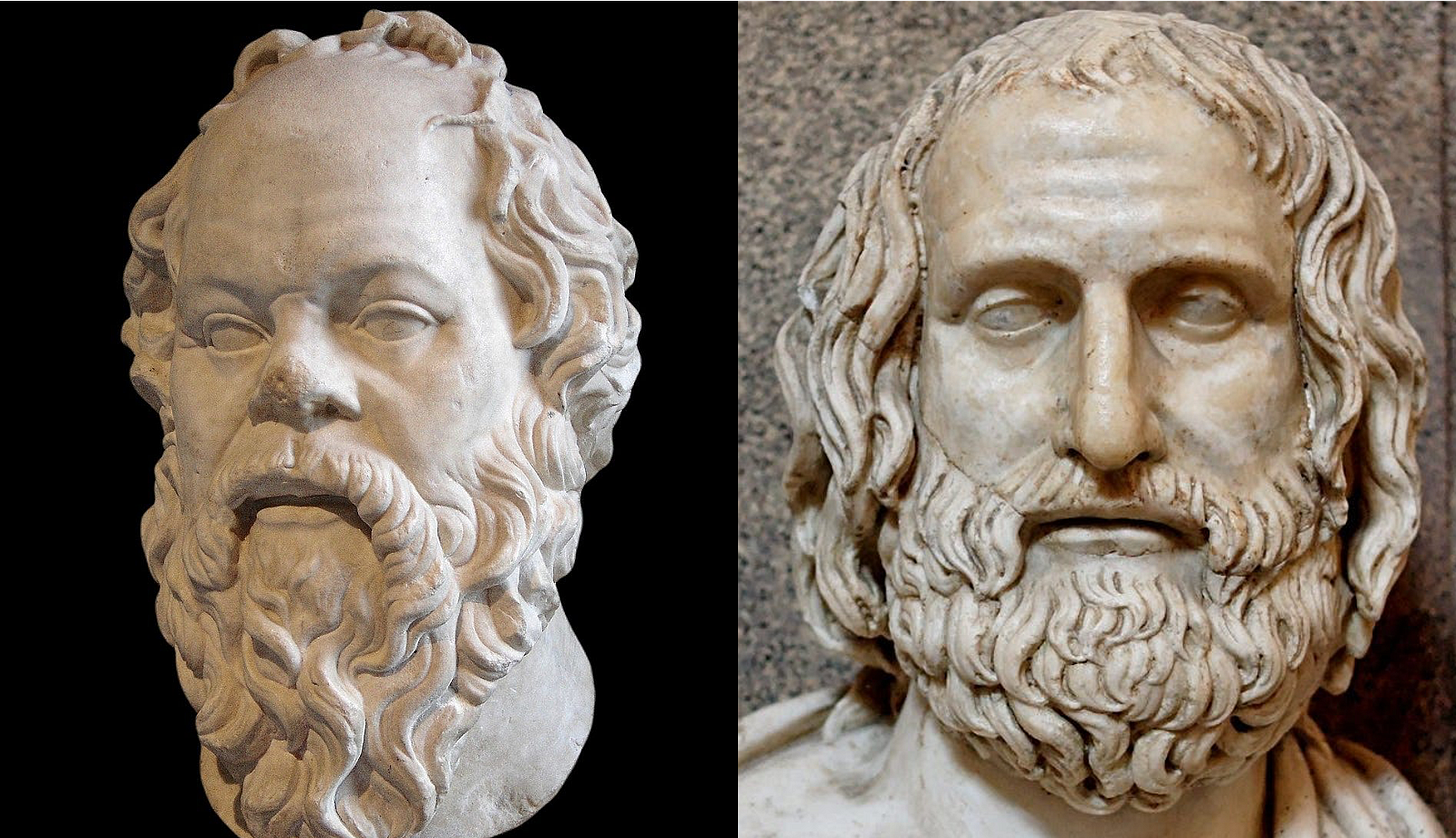

So said Socrates, in Plato’s classic, The Republic. And I’d say most regular people agree with this sentiment. After all Socrates himself said it… a pretty good source of expertise. And the idea of “objective truth” seems like plain common sense.

Today we remember Socrates as the foremost ancient Greek philosopher, but he was far from the only one. Back in his day Socrates debated an older and, some say, wiser philosopher: Protagoras. Protagoras held a different idea of truth, summarized in his famous quote:

“Man is the measure of all things.”

What an eloquent line! Maybe too eloquent. In fact it’s a kind of subversive quote. Protagoras is saying that the truth is relative… subjective, imprecise, varying according to the individual. Your notion of truth may be different from mine. Personally, I recoil from this idea. After all, shared truth is how we communicate and understand the world. Shared truth is necessary for human progress.

So I always took the side of Socrates in this eternal debate. But these days I’m reconsidering my own viewpoint. In a world of individualized media and AI-driven content, it seems more than ever that truth really is relative. Along with David Hume, Protagoras is a prophet for the age of artificial intelligence. For just as AI has upended our concepts of human intelligence, AI will soon scramble our concepts of truth.

The Rise of AI Slop

For me it was waterfalls. I fish in the rivers of western North Carolina and I’ve gotten to know a few local waterfalls, simply by having stood nearby them for hours while fishing. So it seemed natural to see a random social media post labeled “Upper Whitewater Falls, NC.” I’ve been to Upper Whitewater Falls in western North Carolina. In fact I’ve hiked downstream from there to Lower Whitewater Falls, just across the border in South Carolina. I even caught a few little rainbow trout in that short stretch of the Whitewater river.

The image online was beautiful and looked generically like a waterfall in this region. But upon closer inspection, the picture bore no resemblance to the actual Upper Whitewater Falls. It wasn’t the same falls, an in fact wasn’t even a decent approximation of it. It was an AI-generated image pretending to be Upper Whitewater Falls. A day later, I saw an image claiming to be Rainbow Falls. Same thing. It wasn’t real. It was AI-generated content without truth to it, naming itself for a real place which in fact it did not resemble. Upon review, I’ve realized a large percentage of my social media feed consists of AI-generated fakes. Or as they are becoming known: AI slop.

AI slop is a preview of things to come. Today it’s waterfalls; but tomorrow it will become much much more. It’s coming for images. It’s coming for videos. It’s coming for stories and quotes and books and texts and attributed articles of news and opinion. It’s coming for our information… all our information. And it’s gonna be hard to stop.

Why fake waterfalls? Clicks and views of course! If the image took my attention for an instant, it was worth doing for its anonymous creator. If future bigger sloppier AI can capture more of my time, then it will. In fact the question “why” is wrongly posed. The proper question is: why not? It’s pretty easy to do, and nothing’s stopping anyone from doing it. The good ones will simply apply AI in an automated script to build and post zillions of slop images and videos, on every topic under the sun, to everyone.

In a world of digital information unchained from truth, there’s no limit to the scale or reach or penetration of AI slop. And so I expect AI slop to infect the majority of information in the world in the very near future; let’s say within the next several years. Waterfalls are just the beginning. Next it will be photos of families on vacation. News articles. Speeches given by senators and presidents. Videos of news events.

AI slop encompasses the realm of so-called “deepfakes”. But “deepfake” seems a misnomer here. The term deepfake implies a targeted fakery to achieve some specific nefarious goal. AI slop is akin to deepfakes produced by the hypothetical thousand monkeys on a thousand typewriters. It s nefarious but not in a targeted way. It works in volume.

AI slop carries digital information much further from the truth. That much is clear. But the larger question is: what will AI slop do to us?

The Measure of (AI-Generated) Things

AI misinformation is like the tide. We can’t stop it. But I’m not interested in AI misinformation for its own sake. I’m interested in us… in people, in humanity. How will we change in the future when we’re exposed to this slop pervasively across our information spectrum? What does AI-driven un-truth do to us?

The pessimistic view says that we will cease to discern between truth and fiction; because doing so is hard and we’re not equipped to do it. That’s a scary idea which is somewhat in motion already. If you’re a pessimist you have some reasons to be depressed; not over a single falsely-attributed waterfall but over the loss of truth itself. In the words of philosopher Hannah Arendt, speaking about propaganda from the holocaust era:

“If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer.”

Ouch. It feels that way sometimes, doesn’t it? Maybe AI slop will make us cynics.

I am an optimist however and I don’t believe that totalitarian model is the future. To some degree at least, we humans filter information as we consume it. Turning again to the Nazi era, it was said that a major factor of Hitler’s rise (and Franklin Roosevelt’s as well) was the rise of broadcast radio in the 1920s and 1930s, which brought authoritative voices into millions of households for the first time. In the 1930s, no one had developed a radio filter-of-the-mind. And so information entered the ear and was written straight to our memory, no questions asked. But our societies and our minds have evolved since then. We have learned to apply the proverbial “grain of salt” to what we hear. We filter information. That goes for radio; and it goes for social media. We can filter AI slop, not technologically but using the power of our human faculties to label it before it enters our minds, with some foresight and some effort.

For example: a wrong version of the Arendt quote above has circulated recently in my social feed. But because I know AI slop is pervasive, I anticipate this can happen. Therefore I did some research to source the correct version before sharing it above.

So: maybe AI slop will make us skeptics.

AI slop might also build a stronger market for verified information, which has been vetted to scrub out AI slop before we see it. After all, credible news organizations do that now with other forms of fakery, for example by verifying information from multiple sources and shedding light on self-dealing when possible. Policing for AI slop, as a human exercise, can be done by decent professional journalists. Who knows, maybe society will re-discover the value of the independent and trustworthy press which self-enforces basic rules of truth-telling. We might even get our news from newspapers again!

So: maybe AI slop will make us more educated news consumers.

Human Truths, AI Power

But we have bigger issues than just AI slop. The rise of AI also represents the rise of tech industry fortunes, and the power that follows such fortunes. The nexus of tech, power, and money creates the emerging tech broligarchy. And whether we like it or not, these perpetually-adolescent proto-adults will control the future of AI. To think about their impact, we can turn to recent philosopher Michael Foucault.

In matters of truth, Foucault was a relativist, plainly on the side of Protagoras. His philosophy included some complex frameworks for how truth is arbitrated in the context of society. Foucault added an important twist to the relativism of Protagoras: truth is not just relative, but also defined and shaped by power. Truth reflects the power structure of a given society, the rules of power in a given age, and the will of powerful people who define truth itself. If the objective truth of Socrates was a calming ideal, Foucalt’s truth feels to me like a slow nightmare. In Foucalt’s own words,

“Truth isn’t outside of power… Each society has its regime of truth, its ‘general politics’ of truth: that is, the types of discourses which it accepts and makes function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true and false statements, the means by which each is sanctioned; the techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true”

Read the quote above, line by line, and ask how it applies to a future where our information space is shaped by AI-driven gatekeepers..where we take our truth from AI chatbots, AI search functions, AI agents, and more AI tools written and verified by AI coders. In that near-term future world, what will be our society’s “regime of truth?” What are the “mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true and false statements?” What are the “techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth?” Who is “charged with saying what counts as true?” As AI reaches into every corner of our digital world, these answers will be dominated by AI.

Will AI deliver to our screens the objective truth of Socrates? I’m not betting on it. We know that large language models hallucinate and make mistakes. Recent research also shows that they deceive us purposefully from time to time. And that’s when AI is trying to do it’s best. What about when it’s used to directly promote the agenda of its human creators? (Which is occurring already today in some instances.) When all our questions are answered by AI, and AI in turn is controlled by tech industry billionaires, the truth gets warped along the way.

What can we do? The problem is daunting. There are emerging mechanisms to govern and control AI, so that it is developed and used responsibly. These frameworks are proliferating among a wide cohort of good-governance types around the globe. But to gain the benefits of good governance, we must first value governance. And the value of such governance takes some time to reveal itself.

To borrow a metaphor I heard from an AI tech entrepreneur: governance for AI is like brakes for a racecar. It doesn’t create speed by itself… but you can have a much faster race-car when you invest really good brakes. That kind of nuanced insight has not yet fully emerged in the tech industry… for now everyone’s just building stuff to go as fast as possible. Over time, will the the public will value well-governed and well-trusted AI? I sure hope so. Otherwise we’re all on a fast racecar ride into an information dystopia.

So what exactly is “well-governed and well-trusted AI?” It’s not easy to define… it may be different for me than for you. Sigh. There’s Protagoras and his relativism again.

Back to the Question

I don’t think Socrates was entirely wrong. In some important spheres of human activity, we’re able to seek and find objective truth. Mathematics and physics are good examples. These realms are the home-turf of the Socratic viewpoint. Actually my background is mechanical engineering…. which is roughly akin to applied physics. We mechanical engineers may not be the most interesting lot, but we know the value of objective truth. If a motor produces 300 horsepower, we can calculate or simulate or measure that value, and we can agree to it… or agree to update it based on what the data tells us. We’ve agreed on what that truth is, in our little corner of the world. As AI approaches, maybe I’ll just stay in my lane and not worry too much about the rest.

But I’ve come to accept that in complex matters of economics, justice, law, government, and so forth, a common truth does not exist. And never will exist. In these matters, much opinion is bound up with truth, and it’s not feasible to pull them apart with any objective precision. Relative truths are not the exception, but the norm. In the near future, AI will generate a kaleidoscope of relative truths through which individuals may view the world. In the future, every individual may settle into his or her own unique AI-generated reality. Protagoras was right.

Michael Foucault was also right. The definition of truth will ebb and flow according to the power structures of society. And therefore: in the future when AI becomes very powerful, AI will tell us what the truth is. It will be up to us to believe it, or not.

What to do? Despite the coming tidal wave of AI-arbitrated-everything, there is hope. We can use the same mechanisms we employ against AI slop to protect against AI mistruth in general. We can employ bit of skepticism, a bit of cynicism, and a will to look for the truth. We can govern our AI with common-sense rules rules and frameworks… and demand others to do the same.

Most of all, we can open our mind to different viewpoints, and be active and curious about what the truth is. In this matter we’re wired differently than AI, at least for now. We’re curious by our nature. We can look up a quote twice or ten times. We can read and consider ideas from differing points of view and draw nuanced conclusions based on what we read. We can read our philosophy books!

And we can view our waterfalls in person from time to time, to know how they look, and just to make sure they’re still there.

A great article to pause with and deliberate in peace and tranquility because it will be a core issue in everyones life going forward in the present future.

This is an interesting post. However, can we honestly avoid being changed by our tools? As a quote attributed to Marshall McLuhan says, “We become what we behold. We shape our tools, and then our tools shape us.” I find it hard to imagine that tools like LLMs won’t change us over time. We’re likely to outsource more and more tasks to them in the name of convenience, time-saving, and shortcuts. It will start slowly—just one task here or there—and then become a habit. I can see how getting a quick answer in the name of productivity or even under external pressures from organizations or peers would become essential. After all, most organizations don’t care whether their employees are learning; they care about productivity and output quality.

As you have also said, the critical question for me is whether we’ll trust the outputs of LLMs at face value or apply common sense, intuition, and tacit knowledge to assess whether they are true. My concern is that the more these tools become part of our work and lives, the more we’ll trust them, and the more we’ll outsource our thinking. I can see this happening gradually, as the convenience of these tools makes them indispensable, and we no longer need to question their outputs.

I think the shift will happen in how we approach questions and answers. As I see it, "why" will become far more important than "how." Instead of focusing on how to get the answers or solve a problem, we’ll need to focus on why we trust the output or a solution. But the danger is that we might stop asking "why" altogether. If we rely too heavily on tools that provide answers instantly and effortlessly, we might lose the habit of questioning and critically evaluating the information we’re presented with.

Another point I’ve been considering is how external pressures—whether from organizations or peers—may accelerate this reliance, and people might feel compelled to use these tools uncritically over time to keep up with expectations. That’s why I think it’s so important to encourage a culture of questioning and exploration, even in environments that prioritize speed and output over deeper learning.

Staying "in the loop" as humans will require effort and vigilance. I think we need to treat AI tools like collaborators—not infallible authorities. That means questioning their outputs, cross-checking information, and applying our judgment.

I will end with a quote from Nicholas Carr: “As we come to rely on computers to mediate our understanding of the world, it is our own intelligence that flattens into artificial intelligence.”

It is a powerful reminder of the cost of over-reliance on tools at the expense of cultivating our minds.